Rooted

An installation by Leonard Ursachi, curated by Matilda McQuaid.

July 17 – November 30, 2025

Rooted

For decades, Ursachi has wandered the environs of his DUMBO studio, salvaging driftwood lodged on the East River’s shore, cobblestones displaced by construction, discarded remnants of the old Brooklyn piers and railroad line.

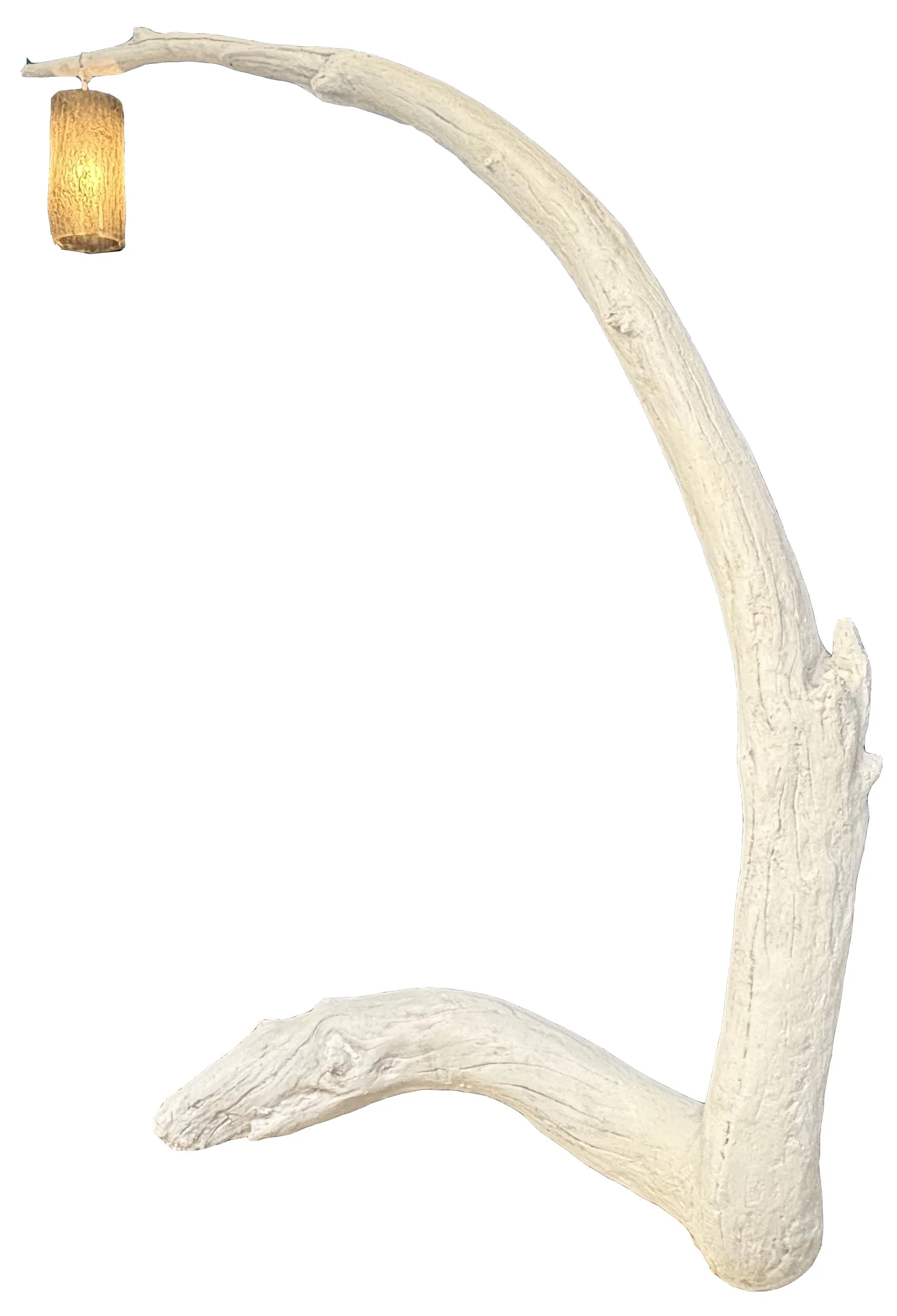

A white table, chair and lamp sit together in the center of the space, evoking community and shelter. Palimpsests, they bear traces of their source: the lamp and table were cast in cement from driftwood and the chair from planks from a long abandoned DUMBO pier. On the gallery walls are drawings, watercolors, and small sculptures and salvaged artifacts.

According to curator McQuaid, “When Leonard defected from Romania, he could not return. His art speaks to the nature of home and the physical, embedded essence of memory. Rooted is a gathering of objects he has collected and transformed, each with a deep sense of place and time, both past and present.”

Rooted Chair, 2025. Cement. 67” high x 17.75” wide x 26” deep.

Rooted Table, 2024. Cement. 24” high x 24” wide x 20” deep.

Rooted Lamp, 2025. Cement, electrical lamp fittings, translucent pigmented resin. 84” high x 6” wide x 18” deep.

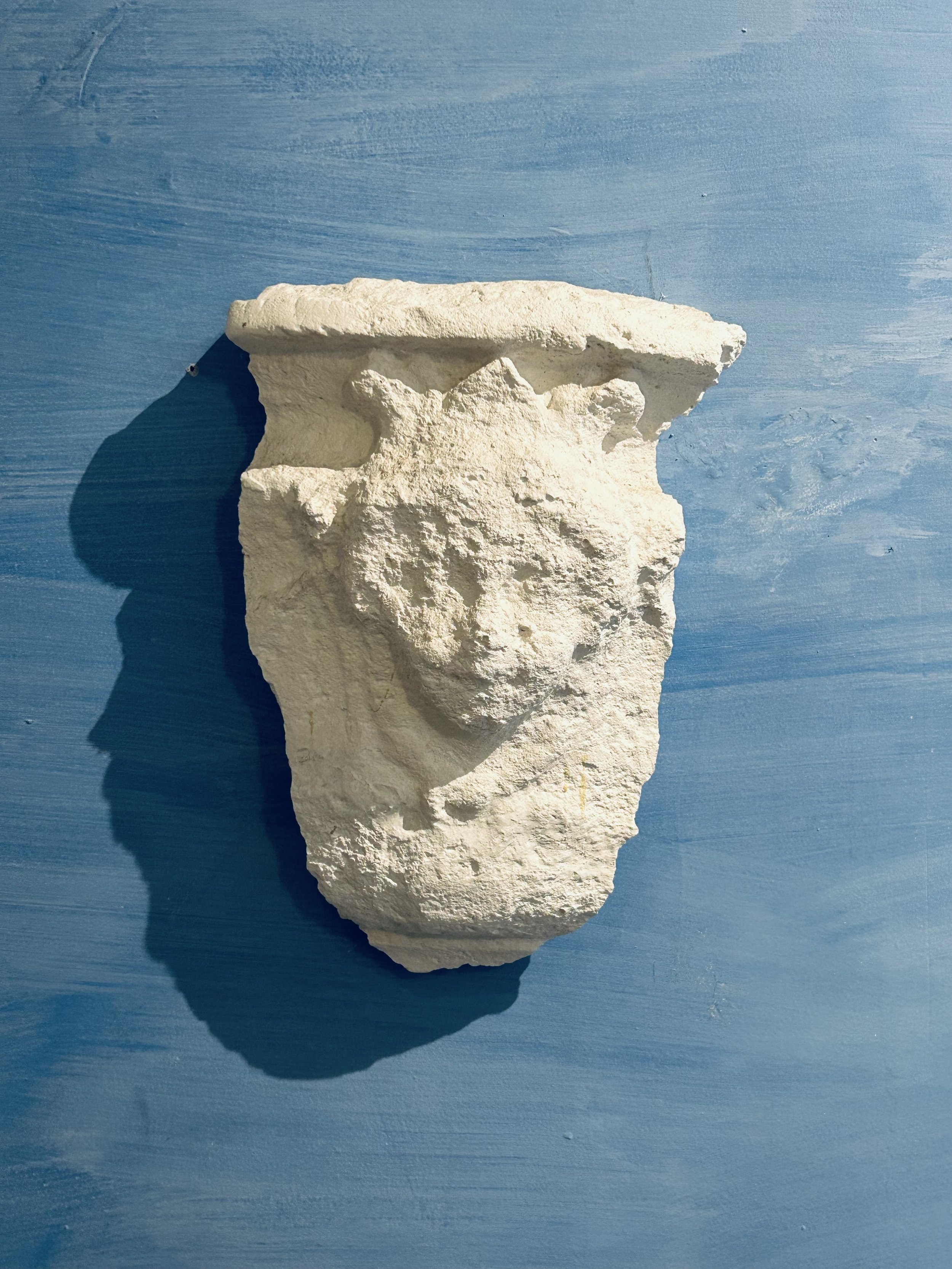

Ursachi cast Trace, with its cherub head, from a French limestone urn that dates to the 1800’s.

“The history of art is a multiplicity of stories, many forgotten or repressed in favor of the dominant narrative of the time,” he says. “Cherubs – powerful creatures that first appeared in Middle Eastern mythology and religions – evolved over millennia into malleable, Western signifiers of Eros, abandon and joy, in kitsch and ‘high art.’”

Fat Boys

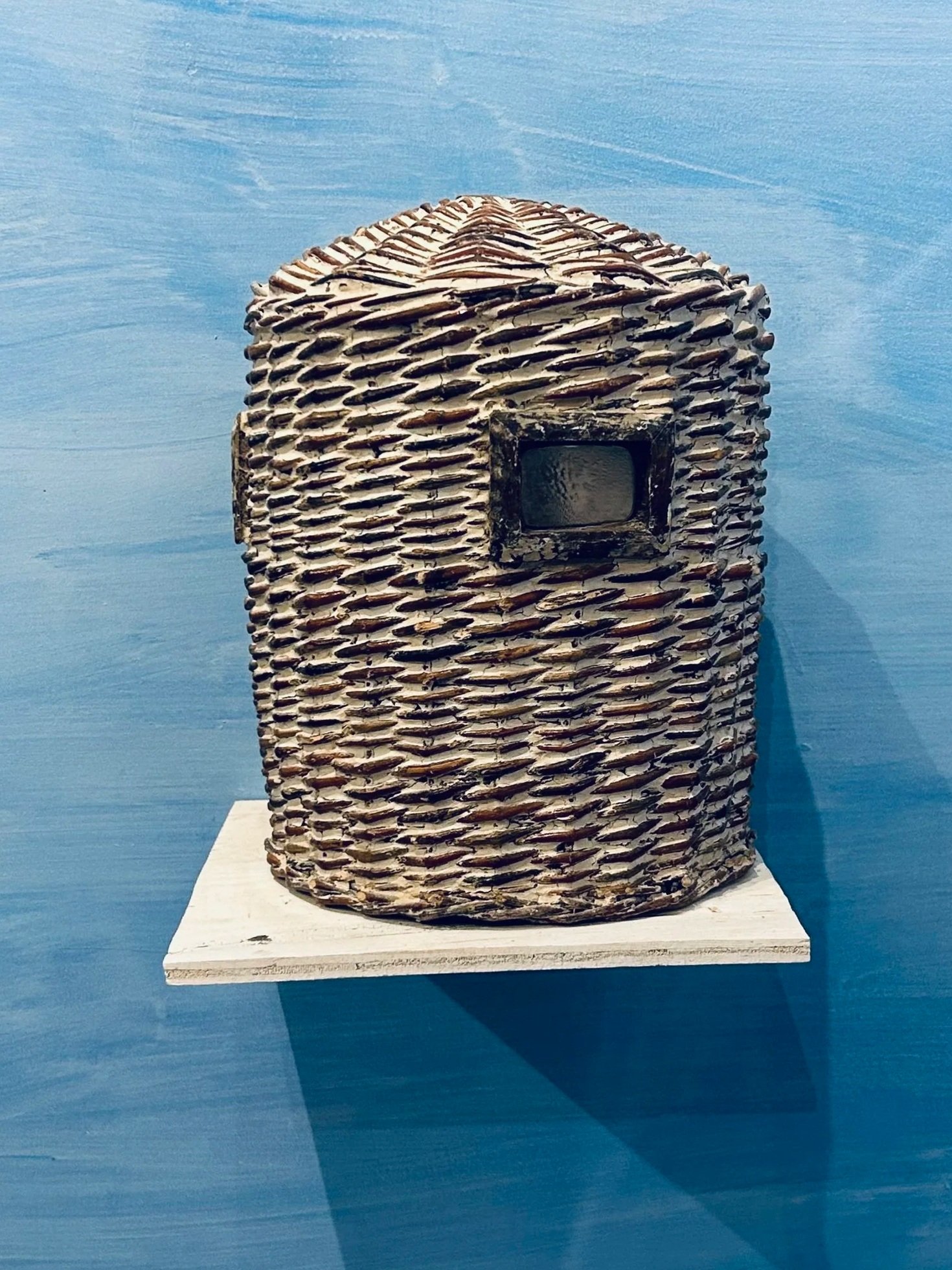

Ursachi grew up in Communist-era Romania when citizens were not allowed to leave their country. Bunkers dotted Romania’s borders. Some were remnants of WWII, but many were built during the Cold War to instill fear of outsiders – a government-sponsored bunker mentality.

Ursachi has created numerous “bunker” sculptures – woven from willow branches, covered in turkey feathers, surfaced in ceramic tile. Says Ursachi, “My bunkers aim to evoke not only chauvinism and conflict, but also nests, refuge, and beauty.”

Ursachi’s Fat Boys belong to his bunker series. The large-scale Fat Boy currently exhibited in DUMBO under the Manhattan Bridge was originally commissioned by the John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida, on whose grounds it was on view for over a year. Fat Boy contains three recessed, mirrored “windows”—referencing a bunker’s embrasures—but Ursachi based its form on a classical Western cherub, or putto. The title refers not only to Fat Boy’s plump, cherubic face, but also to the names of the WWII atomic bombs, Little Boy and Fat Man.

Fat Boy Mask, 2015. Plaster, mirror. 8” high x 7.5” wide x 3.25” deep.

Fat Boy, 2015. Plaster, pigment, mirror, wood base. 8” high x 7.5” wide x 3.25” deep.

Fat Boy (Golden), 2015. Cast rigid foam, mirror, 21 carat gold leaf, wood base. 8” high x 7.5” wide x 3.25” deep.

Fat Boy (Sarasota), 2013. Styrofoam, Styrocrete, pigment, stainless steel mirrors and armature. 118” high x 98” diameter.

Hiding Place

Ursachi created the original, large-scale Hiding Place bunker for a museum in Romania; it was exhibited beside a 15th-century fortress in the Carpathian Mountains, a site that had a profound impact on him as a child. The fortress, with its massive stone walls, was a muscular symbol of war, of “us” versus “them” – symbols that were dusted off and given a fresh gloss by the Communists. Because it lacks a door and its “windows” are reflective shields, viewers can only imagine its interior. With Hiding Place, Ursachi continues his investigation into the world of porous borders, vulnerable shelters, and mutating identities that is the 21st century experience of home.

Hiding Place, 2003. Willow branches, clay, mirrors. 14” high x 11” diameter.

Bunker, 1998. Charcoal, pigment on rice paper. 40” high x 30” wide (framed).

Hiding Place in Tirgu Neamt, Romania, 2003. Willow branches, wood, mirrors. 110” high x 100” diameter.

Hiding Place in Tirgu Neamt, Romania, 2003. Willow branches, wood, mirrors. 110” high x 100” diameter.

Hiding Place in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, 2007. Willow branches, wood, stainless steel mirrors. 98” high x 98” diameter.

Railroad Ties

The DUMBO waterfront was once served by the Jay Street Connecting Railroad, built in 1904 by industrialist John Arbuckle to carry cargo from the waterfront to his coffee warehouses in what was then called Vinegar Hill. It was abandoned in 1959, but several remnants of tracks remain on DUMBO’s cobblestone streets.

As a DUMBO street was being restored some years ago, Ursachi salvaged a discarded railway tie.

Railroad Tie (cast), 2025. Plaster. 21” high x 7” deep x 6.5” wide.

Railroad Tie (original). 21” high x 7” deep x 6.5” wide.

DUMBO Pier Elements

Ursachi’s grandfather Gheorghe Ursachi had been a member of the Romanian King’s elite private guard, served in WWI, was an engineer on Romania’s steam trains, and a union leader. He built his family home with his own hands and carved the solidly graceful oak furniture that filled it. In his twilight years, widowed and paralyzed from the waist down, Gheorghe opened his home to Ursachi, his parents and older brother.

Gheorghe had built a workshop beside his home. When he lost the use of his legs, he carved himself a pair of wooden shoes like Japanese geta. He’d put them on his hands and drag himself, on his belly, from bed to shop and back.

Romania is known as a birthplace of the wheel; wheeled vehicles from around 3950 BCE were unearthed in the Carpathians. In his shop, Gheorghe carefully crafted elegant, perfectly circular wooden wheels. One after another. Over and over again. He sought, salvaged and stored the optimal species of wood for his circular creations, which, as far as Ursachi is aware, never left the shop walls that they adorned.

The rigid, robust pier elements in Rooted – which may be 200 years old – remind Ursachi of Gheorghe. The first ferry service over the East River connected Brooklyn to Manhattan in 1642, necessitating a modest pier. In 1883 the Brooklyn Bridge opened and soon, DUMBO’s waterfront was blooming with piers. By the time Ursachi moved to Brooklyn in late 1988, the piers – and the waterfront – were decayed, abandoned. He stepped cautiously across the exposed tips of old posts to salvage pier sections that dangled into the water, and stored them in his studio for decades.

For Rooted, Ursachi cut three sections from a salvaged pier element, cast them in concrete, and assembled them into the Rooted chair.

Bollards

Bollards are mooring posts that secure arriving ships to wharves. Ursachi created a series of sculptures and drawings based on a 19th century bollard on a Brooklyn pier. The earliest American bollards were decommissioned army cannons buried muzzle first into wharves, with a third of their barrels and rounded butts above ground. Over centuries, bollards have moored countless ships to Brooklyn’s piers. Some carried slaves, some carried immigrants, some carried silk and cotton and tea.

Today, bollards have migrated from shores to streets, where, squat and thick, they stand sentry before post offices, banks, and religious buildings, set close together so that no vehicle can pass through. Bollard as protector; bollard as deflector.

Bollard Drawings, 2024. Watercolor on paper. 15” high x 12” wide (framed).

Bollard, 2020. Pigmented resin. 32” high x 24” wide x 24” deep.

Installation view, Unmoored - A Family Portrait, 2022 at Canton Projects.

Armature slices

The well is a shared resource and gathering place. Its iconography is mythic – the source from which life and knowledge spring; a receptacle for our dreams and desires. Around the world, communities still depend on wells, the health of which is affected by conditions that originate both locally and across the globe: pollution, industrial waste, climate change, wars.

In 2012, Ursachi created Well for Cadman Plaza Park in Brooklyn. He cast blocks for the wellhead in translucent, water-blue acrylic embedded with discarded plastic bottles. He made the mold from an antique cobblestone retrieved from a DUMBO street under repair. He salvaged driftwood from the East River to construct the bucket, pole and lever, and placed mirrors into the wellhead and bucket, for reflection.

Ursachi hollowed out the driftwood he used for the pole and inserted an armature that he made of steel and injectable foam. In Rooted hang three horizontal slices through the pole, revealing the reinforcement within the driftwood.

Slices, 2012. Driftwood, steel, foam. 8.25” high x 8” wide x 1.5” deep; 8.5” high x 9.5” wide x 1.5” deep; 8.5” high x 9.5” wide x 2” deep.

Well, 2012. Driftwood, rope, steel, foam, pigmented resin, discarded water bottles.

The Artist and the Curator

Leonard Ursachi is a Romanian-born American artist. He grew up under a dictatorship, from which he defected, and spent years border-hopping before settling in New York. France granted him political asylum and a scholarship to study art history and archeology at the Sorbonne. His art reflects our contemporary world of porous borders, vulnerable shelters, and mutating identities.

Ursachi is the founder of Canton Projects in DUMBO, New York.

Visit his website.

Matilda McQuaid has been a curator in New York for more than thirty-five years, where she has organized major international exhibitions on architecture and design for institutions such as The Museum of Modern Art. She also writes and lectures on architecture and design.

McQuaid has authored numerous books, including Shigeru Ban, Phaidon Press; Lily Reich, Designer and Architect, H.N. Abrams; Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles (with Cara McCarty), Museum of Modern Art; and Scraps: Fashion, Textiles, and Creative Reuse: Three Stories of Sustainable Design (with Susan Brown), Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.